Labor Economics

Divvy: Bike share in Chicago

Less than a year ago, the city of Chicago rolled out a citywide bike system called Divvy. As you walk around the city, you see bike stations that look like the one below in the post. I took one for the first time a few days ago.

Less than a year ago, the city of Chicago rolled out a citywide bike system called Divvy. As you walk around the city, you see bike stations that look like the one below in the post. I took one for the first time a few days ago.

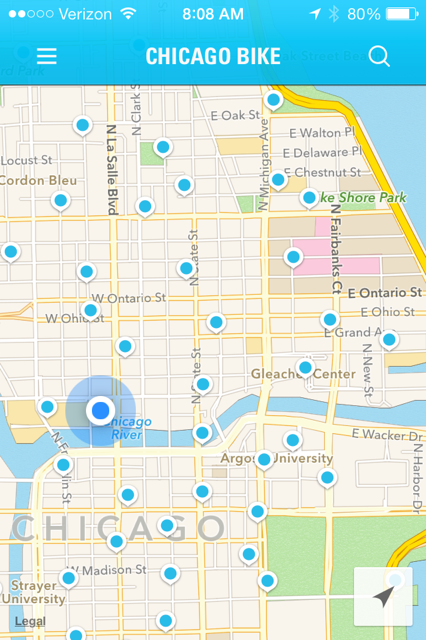

I walked out of an Applie Pie Contest with friends in Bucktown feeling full, and was ready to get back to River North for an evening yoga class to work off the food. But there were no cabs immediately around and public transportation from Bucktown to River North isn’t great. The subway and the bus ride both require  a switch and that can be tricky if you don’t time it right on the weekends. So I took out my phone, downloaded the Divvy app, and looked to see if there was a station close by. Of course, the moment I put my head up and started looking around, I saw one less than a block away before the app was even downloaded.

It works a lot like a public transportation system. You pay a small fee and can get a bike for a full day. You can pay for it right the kiosk. Then pick what number bike you want. When you pull the bike out of the rack, it’s yours to ride.  You can take it anywhere you want, so long as you dock it in any station when you’re done (like RedBox). When you arrive at your desination, you just put the bike back in the rack and it locks itself. And best of all there are lots of locations around the city as you can see in the photo below.

The bikes felt really secure and sturdy. They also have a built in lock system so you can lock it up. They’ve got gears, sturdy breaks, and a basket for shopping.

There are probably some safety concerns. I didn’t have a helmet on me. Any entrepreneurs out there that want to work on an inflatable helmet that fits in my pocket? I’d totally fund the idea. I had a friend tell me she had an extra, but I was already biking by that point. Likewise, cars and cabs can be tough on roads with smaller bike lanes or roads without a lane. But ever since the roll out of Divvy, a lot of roads have put bike lanes up so I did my best to stay on roads that felt secure.

In th end I made it home fast, safely and on time to make the class. While public transit is sometimes the best way to get around, sometiems Divvy is easier.  And best of all, it was an awesome ride!

The (not) Tipping Point

Sushi Yasuda, an expensive restaurant in New York, recently made the choice to eliminate tips for its waitstaff.

Sushi Yasuda, an expensive restaurant in New York, recently made the choice to eliminate tips for its waitstaff.

Yes, you read that correctly. It’s true.  No more tips. Instead of spending 30 seconds after getting your check and pondering how much to write on the tip line, instead you just pay the bill and leave. It’s that simple.

The good thing about it is that there is no confusion.  On every receipt, the restaurant has the following  statement:

“Following the custom in Japan, Sushi Yasuda’s service staff are fully compensated by their salary. Therefore gratuities are not accepted.â€

This example is rare because the vast majority of restaurants do not do this … at least not in the U.S. In the US, tipped employees are paid minimal amounts and customers are accustomed to paying at least 15% extra, even when the service is not great. But in this case, Shshi Yasuda actually compensates the staff with more money (and with benefits) so the tip is not needed.

Other higher end restaurants are considering as well, but there is no word on whether any will adopt the new model or if less expensive restaurants would consider it.

On one hand, I think it would be great not to have to worry about tipping.  Get your check, swipe your Visa, and head out. On the other hand, there is the obvious risk that this will make prices appear too high, even if the final bill would be the same once the tip had been added.

I’m sure all the MBAs of the world have opinions about this.

Dean Blount Rings NYSE Closing Bell

On Friday, January 14, Dean Sally Blount of the Kellogg School of Management went to New York to visit the NYSE.  Together with the long time Kellogg alumni, and other alumni in the financial services industry, the Dean had the unique and memorable opportunity to take part in ringing in the closing bell.

On Friday, January 14, Dean Sally Blount of the Kellogg School of Management went to New York to visit the NYSE.  Together with the long time Kellogg alumni, and other alumni in the financial services industry, the Dean had the unique and memorable opportunity to take part in ringing in the closing bell.

By many accounts, the movement of the financial market has been one of the most defining stories of the last couple of years.  First because of the recession, and now because the financial market is on the rise again. Thanks to the joint effort by the Kellogg School of Management and Kellogg’s very own Alumni Club of New York, Kellogg had a chance to participate in the story.

Not only was this a fun opportunity for Dean Blount, but it’s also be good for Kellogg, as it should help to continually solidify the school’s ties to the finance industry.

Click here to find the actual video of the dean ringing the bell.

How Is The Economy These Days?

Two years from now, many of us graduating from business school will look back on the last few years and compare those economic times to those times at graduation. I applied to business school in 2009, which at the time was the hardest year for ever for MBA applicants. It was also the year where round one applications hit a record high at a number of top schools and the associated yield rates expanded class sizes to unprecedented levels (click here for my post on the 2009 economy). At the same time, recruiting in the legal world last year also took a plunge, and students were scrambling all year to find the summer associate positions that used to be guaranteed upon graduation from a top school. The question is, how is the economy doing these days?

Two years from now, many of us graduating from business school will look back on the last few years and compare those economic times to those times at graduation. I applied to business school in 2009, which at the time was the hardest year for ever for MBA applicants. It was also the year where round one applications hit a record high at a number of top schools and the associated yield rates expanded class sizes to unprecedented levels (click here for my post on the 2009 economy). At the same time, recruiting in the legal world last year also took a plunge, and students were scrambling all year to find the summer associate positions that used to be guaranteed upon graduation from a top school. The question is, how is the economy doing these days?

Well that’s one question that’s on everyone’s mind, because this past weekend was labor day, and so many people were talking about jobs and recruiting all across the country. Â A lot of people are still referencing the recession that officially ended in 2009 and left millions of Americans without jobs, many of which haven’t found their way back into full-time jobs today. The period is still considered one of the worst economic periods in recent history, if not the worst.

For factual reference, the Department of Labor statistics say that more than 6 million people have been out of work for the past half a year, which is about double the count of 3 million a year ago. What does this mean? Maybe it suggests that things have not gotten much better, and in fact actually gotten worse? Â Or maybe it suggests that the time it takes for the economy to recover will take a lot longer than we all think? Maybe it even suggests there were a lot of issues already swept under the carpet that were uncovered when everything came to a halt. Personally, I suspect all three probably play at least a small role (click here to hear what Robert Reich, former Secretary of Labor, said on Labor Day)

But the good news is at top MBA programs, like Kellogg, things seem to be on the rise. Incoming MBA students are pretty optimistic about their chances this year, not only here in Evanston but also across the U.S. at other top schools, which is the word I get from my friends. At law school things are finally starting to improve. This year is shaping up to be better than last year, and my classmates at Northwestern Law are still interviewing with firms in all geographies — Chicago, NYC, LA, DC, and the Bay, to name just a few — and others have already received offers from the very top firms.

On the other hand, it still seems like the recession was only here yesterday, so I think a lot of people aren’t quite “sold” on the idea that we’ve “recovered”. That’s especially true in law school, where the students are more risk averse, and where it was only last year that students felt the aftershock of the worst legal recruiting season ever.

It will certainly be interesting to see how everything plays out both at business school and at law school over the next few months. But one thing to keep in mind to all those applying to graduate school, to those currently in graduate school, and those already in the workforce post-graduate school, is that JD and MBA programs only represent a small subset of the population. The majority of the world isn’t afforded the opportunity to obtain a JD or a MBA degree, let alone both degrees and from a top school. Â And so instead of thinking just about just MBAs and JDs, we should also consider the economic implications of the economy more broadly.

In the end, it’s in all of our interest to reduce unemployment and obtain a more stable workforce. Because having a stronger and more stable economy depends on it.

Law School Recruiting Begins Next Week

Despite many of the public interest goals applicants write about in personal statements, most students at top law schools usually end up spending a few years at a big law firm. One reason is because law firm salaries are high and help students to pay down their loans. Another reason is that students gain a measurable skill set that employers value, both in the legal and business worlds. So for months, students read cases, outline, take exams, and aim for the best grades possible before eventually going through the recruiting process and interviewing at law firms all around the country. Well, that time has finally come for Northwestern’s class of 2012. And next week officially marks the beginning of law school OCI.

Despite many of the public interest goals applicants write about in personal statements, most students at top law schools usually end up spending a few years at a big law firm. One reason is because law firm salaries are high and help students to pay down their loans. Another reason is that students gain a measurable skill set that employers value, both in the legal and business worlds. So for months, students read cases, outline, take exams, and aim for the best grades possible before eventually going through the recruiting process and interviewing at law firms all around the country. Well, that time has finally come for Northwestern’s class of 2012. And next week officially marks the beginning of law school OCI.

At long last, twelve months after moving to Chicago and embarking on the long and difficult journey of 1L, law school students at Northwestern will finally start to go through the OCI (on campus interview) recruiting process in just a few days. Unlike business school, where recruiting officially begins in January after students have a chance to get settled in, meet a larger variety of employers, and prep with classmates for case-based interviews, in law school, on-campus interviews officially begin in mid August before students ever step foot on campus. In times past, this was probably ideal for students, because it allowed them more time to prep for interviews in the summer before the hustle and bustle of classes started taking up more time. But now, even as the economy continues to improve, there is still a lot of uncertainty regarding recruiting, so there is not really an ideal time.

The good news for the class of 2012 is that schools and employers are projecting an increase in the number of summer associate positions available next summer as compared to last year, but nothing can be said for certain. First, the projections are based on the assumption that the economy continues to improve and doesn’t take a quick turn for the worse. It also assumes that the attrition rates continue at a normal pace and that firms haven’t decided to use more slots than normal on laterals or 3Ls looking for jobs.

Still, it’s likely that the recruiting numbers will increase this year given the number of employers who are coming to Northwestern and going to other campuses. After all, the number have increased dramatically, despite the fact that firms are being extremely conservative with their hiring decisions these days.

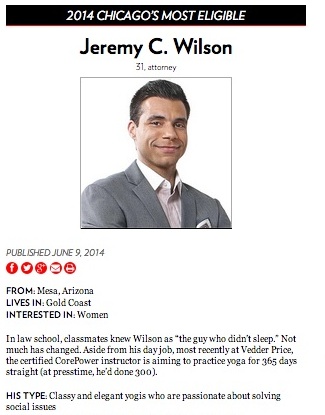

My 1L firm Vedder Price looks forward to hosting a summer class in the summer of 2011, and I look forward to seeing if anyone from Northwestern will join the firm. For the summer of 2010, the firm did not have an official class, but that was mostly because the firm wanted to focus on current employees and ensure that everyone in the class of 2009 had a spot at the firm upon graduation. And fortunately for graduates, the firm delivered on its promise, and everyone from the previous year ended up having a chance to go back to the firm.

But for a lot of other firms, there’s still the “elephant in the room” as students may wonder what happened to the employees who were recently deferred, laid off, or not given offers, just one year ago, before firms started increasing hiring again. But I suspect this is a question that likely won’t come up, which in my view may be for the best given that it’s hard to point fingers at anyone given the economic times that we’ve seen over the past two years. In fact, things were so bad that even many of the best-managed businesses and law firms couldn’t foresee the economic crisis coming, a fact which is supported by leading economists and recent supreme court opinions (Click here for the In re Citigroup legal opinion)

Fortunately, times are better now, and law firms and students are experiencing the best employment prospects that they’ve seen in a couple of years. This is great news for the class of 2012 and hopefully good news for those in the class of 2011 that are looking for new opportunities this year. It will be interesting to see how some of the numbers play out over the next few weeks during OCI.

Best of luck everyone with your interviews.

And stay tuned for more careers and recruiting details and news over the next few weeks.

Working On A Presentation for Latino Legacy Weekend

Have you ever seen a presentation where the audience didn’t pay very close attention, or where they pulled out their Blackberries instead of listening? I have, and I suspect you have too. That’s because delivering good presentations can be tough. They often lack direction, don’t evoke emotion, and don’t truly connect to the audience. Well, just the other day, I found out that I have the challenge to do all those things at an upcoming conference next week here in Chicago.

Have you ever seen a presentation where the audience didn’t pay very close attention, or where they pulled out their Blackberries instead of listening? I have, and I suspect you have too. That’s because delivering good presentations can be tough. They often lack direction, don’t evoke emotion, and don’t truly connect to the audience. Well, just the other day, I found out that I have the challenge to do all those things at an upcoming conference next week here in Chicago.

Just days ago, I chatted with the organizer of the inaugural Latino Legacy Weekend Seminar. The seminar is hosted by my good friend, former congressional candidate, and current US Department of Treasury team member Emanuel Pleitez. Emanuel is a great guy, and like a lot of the folks I know, he’s definitely making things happen, and keeping me on my toes to try to do the same.

The event will host students and leaders from all backgrounds and professions – law, business, finance, policy, arts – and bring them together to think about their passions, ideals and biggest concerns. “The Weekend’s driving question is: What legacy will we leave? It’s an opportunity to step outside of our fields and pause our lives to challenge one another to think big.”

And in my view, this event will not only be a good opportunity to talk about this question but also to share critical information and personal stories with each other. Discuss our passions, goals, and dreams, and connections. And then stay connected so we can help each other as we’re in pursuit.

I haven’t finished my presentation yet, but I’ve decided that I’ll be presenting on Labor Economics and the state of the labor force in the Latino community. There’s a lot of good stuff out there. But more importantly, as I continue to say here on my website, I believe that the labor force is the big issue of our time.

I think the key to giving a good presentation will be engaging the audience. And compelling them with interesting information. Fortunately my topic lends itself well to that. But I plan to spend the next week or so figuring out how to be effective.

In a recent article I read that the human body is capable of experiencing over 5,000 emotions. But in the course a single work week, most people only experience a dozen of them. To me, means there’s a lot of opportunity to evoke emotions that people tend not to have because they spend so much time on work, family, and other day-to-day things. Emotions like fears, vulnerabilities, concerns, and motivations. And that’s what the current economy has done to a lot of people. Made them fear being of out work. Become vulnerable to admit and discuss their fears and perceived failures. Feel concern for friends and family who struggle with those fears. And then find motivation to overcome their circumstances. So there’s a lot to work with, and I hope I’ll be able to come up with something good.

Overall, it should be an interesting event. The variety of presentations should be interesting, the rewards of the conference should be manyfold, and it will be a great way to meet a lot of new people.

As always …Â stay tuned to hear how things turn out!

—

PS I’ll also note, that not only do I have this conference next weekend, but I also have another professional conference in New York City in early June. As such, I’ve decided to dedicate a my posts over the next two weeks to the conferences. Before the conferences, I’ll discuss networking tactics and preparation for speaking to attendees and employers. And afterward, I’ll do my best to journal the nuances of the events. I hope that you’ll check back to read. A lot of people have been writing in recently with networking questions. So I look forward to posting over the next few weeks.

How Much Do CEOs Make? Are You Sure You Added That Up Correctly?

There is a lot of talk about how much public company CEO’s make, especially at companies performing poorly, those repaying TARP money, and those handing CEOs large bonuses, while the business is imploding. Every April, the whole world has the chance to shine a spotlight on these CEO paychecks. That’s because spring is the annual proxy statement season, and calendar-year public companies disclose compensation numbers. This means General Counsels work with JDs at law firms and MBAs at consulting firms to do valuations and finalize their SEC filings. It’s interesting to see how pay can swing like a pendulum from one year to the next depending on firm performance. But perhaps more interesting is the fact that levels also happen to change when they are interpreted by a a different valuation firm. Even in the same year.

There is a lot of talk about how much public company CEO’s make, especially at companies performing poorly, those repaying TARP money, and those handing CEOs large bonuses, while the business is imploding. Every April, the whole world has the chance to shine a spotlight on these CEO paychecks. That’s because spring is the annual proxy statement season, and calendar-year public companies disclose compensation numbers. This means General Counsels work with JDs at law firms and MBAs at consulting firms to do valuations and finalize their SEC filings. It’s interesting to see how pay can swing like a pendulum from one year to the next depending on firm performance. But perhaps more interesting is the fact that levels also happen to change when they are interpreted by a a different valuation firm. Even in the same year.

Just last week, the New York Times and Wall Street Journal published respective lists of the top 200 CEO’s pay packages from last year. But to my immediate surprise, I noticed that each list ended up with pretty different results. Compensation for some CEOs was different on WSJ than on NY Times, and in some cases, the spread was significant. HPQ’s CEO, for example, was paid a total of ~$11MM according to the WSJ though the NY Times reported ~$24MM. But more surprising, and maybe more scary, was that both valuation firms are considered highly-reputable, industry experts when it comes to executive compensation.

Given the resources used for the studies, I didn’t expect to see such inconsistently. In today’s environment, where executive pay is already under scrutiny, and where banks are doing little to help the case, companies have no incentive to make compensation even harder. That said, the herculean task of figuring out executive compensation is critical. Company reputations are at stake and executives will have even less chance in the court of public opinion. And conversely, it would be a real economic breakthrough for economists and businesses to figure out how to balance rewards with incentives.

To that end, below, I’ve provided a few details below about the two studies. I’ve included (A) Links to the studies (B) Information on firms that carried out the studies (WSJ and NYT simply reported the information) (C) A few big picture takeaways (i.e. my opinions)

(A) Links To Studies

1. New York Times Study

(i) Pay Table

(ii) General Discussion

(iii) Valuation Techniques

2. Wall Street Journal Study

(i) Pay Table

(ii) Discussion

(iii) Valuation Techniques

(B) Firms Behind The Studies

1. The NY Times study was put together by a firm named Equilar. Equilar is the undisputed industry leader in compensation research. Its analysts dig through proxy statement for a living, and they tend to be consistent in their approach. Many top compensation consulting firms utilize services from Equilar, and some use them extensively.

2. The Hay Group put together the WSJ study. Its Compensation Consulting group is very good and competes with top firms for projects. However, in my experience, it does not always hang with Mercer, Towers Perrin, Watson Wyatt, and Aon for top clients. I suspect all of the firms here, including Hay Group use, or have used, Equilar quite a bit.

– Comparisons aside, both firms should have more than enough resources and experience to do this study, and the real challenges are (i) finding all the numbers, (ii) maintaining consistency of methodology of those numbers across the 200 companies, and (iii) using a sensible option pricing model to calculate the expected stock value (i.e. black scholes). Not a cake walk by any means, but doable.

(C) What does this mean? For what it’s worth, here’s my opinion:

- Stock compensation is hard to value. There are a large number of assumptions in every calculation, many of which change depending on the effective date and are subject to late disclosure, non-disclosure, or improper disclosure by the companies. It also depends on all the black-scholes assumptions.

- If these expert firms can’t come up with consistent numbers, then the media definitely has no business putting out numbers in magazines and papers, which influences and persuades the general public.

- Similarly, articles bashing “Pay for Performance” should also be assessed on the merits of the research and experience of the researcher. And to be valid, they should be back with a good data set.

- Governance standards for proxy filings still has room for improvement. I suspect they will continue to refine the rules, come up withe more standard approaches, and further incent companies to follow. In the past few years, they’ve made some progress.

But these are all high level ideas, easier written about in a post than driven forward, and easier discussed than executed. Executive pay analysis is difficult, not only because it’s highly-technical and nearly impossible to interpret inconsistent and non-standardized data, but also because many numbers are never even disclosed and because the rules of the game are continuously changing. The good news is that the U.S. has taken strides over the past few years, and they’ve taken leaps and bounds as compared to the rest of the world.

But now that we’re in a bit of a standstill with the economy and there are so many questions about valuation, how do we know that these plans even work? And what can we do to continue to incent executives to drive companies forward?  Well, for one, I suspect companies will eventually figure out a more consistent methodology to use when analyzing CEO pay plans–the SEC can do it’s part by making more targeted rules. But they should also allow the best leaders at companies to continue leading. Not only through developing performance and compensation schemes, but now also by giving them incentive to be creative, innovative and develop as leaders.

That’s because the most successful companies spend more of their time talking about new possibilities and walking down the path of innovation than they do about money. After all look at companies like Google and Apple, where innovation is king! Don’t get me wrong, these guys get paid well and they spend a lot of time coming up with the right pay packages, but that’s not the primary driver. And in the meantime, maybe U.S. companies will finally spend more time thinking about that and eventually find a bit of insight into what really drives CEOs and how to harness that to achieve better results. Some theorists suspect that finding this would lead to even better company performance, suggesting that incentive programs actually destroy intrinsic motivation. It’s an interesting debate.

Good Friday … For Labor and Job Statistics

The US economy added 162,000 jobs in March, the biggest net gain in over three full years. That’s good news right? Well, that depends on who you ask. Some say that it’s clearly good news, and that we’re finally moving in the right direction. But others say that the stats are superficial, and that they don’t address the underlying economic issues. I’m not sure what the real answer is, but one thing is for sure. The job market does seem to have a little bit more life. And sometimes, momentum can be a good thing.

The US economy added 162,000 jobs in March, the biggest net gain in over three full years. That’s good news right? Well, that depends on who you ask. Some say that it’s clearly good news, and that we’re finally moving in the right direction. But others say that the stats are superficial, and that they don’t address the underlying economic issues. I’m not sure what the real answer is, but one thing is for sure. The job market does seem to have a little bit more life. And sometimes, momentum can be a good thing.

Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan recently agreed in an interview with Businessweek and said “there’s a momentum building up†in the U.S. economy and the odds of it faltering have “fallen very significantly.â€Â The Obama administration agreed. White House economic adviser Lawrence Summers said that “job creation will accelerate.” And Christina Roemer, chair of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, said suggested that there’s a “gradual labor market healing.” And so it sounds like there may be a subtle wave of optimism that seems to be lingering.

That is definitely the case at business schools, where although recruiting numbers may be slightly down [(i) I don’t know for sure and (ii) It’s not over yet], they won’t be down by much. And during recruiting season, the students seemed to be pretty confident about their chances. Some of the ones I know did well. Many will be working at banks, consulting firms, Fortune 500’s, and start-ups. Even at the law school, things seem to be trending upward. It’s harder to tell exactly how things will play out, since law schools tend to do the vast majority of recruiting in the fall. But the message I’ve heard from most firms and organizations is that things will at least be a little better. I look forward to reporting the real news this fall.

That said, I don’t think these stories are necessarily compelling.

1. First, the administration has the herculean task of managing the negative sentiment that came from the past two year and balancing that with a more optimistm to keep people motivated and working hard, all while delivering a message that’s both truthful and transparent.

2. And more importantly, it’s not necessarily compelling because (i) the world of MBAs and JDs headed to become consultants, bankers, lawyers, fund managers, and non-profit leaders doesn’t reflect the overall economy. In fact, it’s really only a small fraction of the economy. The average person doesn’t attend a top 10 law or a premier business school nor do they hunt for six-figure jobs in their mid twenties, if ever. So many times, that person may end up jumping through a lot more hoops to get to the “promise land” of finding employment. (ii) And not only do these individuals represent a small percentage of the overall economy but they also have the advantage of undergoing a highly sophisticated recruiting process that starts well before interview season begins. A process where employers have coffee chats, luncheons, mixers, and receptions months before recruiting ever begins. And a process where hundreds of employers accept resumes, come to campus, and interview dozens of students on campus, all day. And sometimes multiple days. So taking a step back and looking at everything from a 30,000-foot, big picture view, I see that it’s a privilege to have the process in place.

So with a 30,000-foot view in mind, here are the objective arguments about the labor force, from both sides.

1. One on hand, the hard numbers from BLS do suggest improvement. (i) In total, employers added 162,000 jobs in March, the biggest monthly gain in three years. That’s always a good starting point. (ii) Manufacturing payrolls have also reportedly increased. (iii) This story is also true for heath care employers, who added ~27,000 full-time jobs and ~40,000 private-sector temp jobs. (iv) Surprising is that construction field held steady for the first time, after losing nearly ~865,000 last year. (v) Further, sources also suggest that the investment banks are finally starting to breathe again, and that broadening their scopes of services has helped them to decrease risk and squeeze out more revenues. (vi) And finally the unemployment rate is still down to 9.7%.

2. On the other hand, context suggests that the grass may only look greener. (i) I suspect we’re all aware that the number of jobs and hence total payroll numbers continue to skydive in financial industry. Venture capital and entrepreneurship numbers also remain low. (ii) However, even the numbers that are improving, according to US News, may really be more related to a reduction in labor force than an improving economy. (iii) But despite these more nuance calculations, even real growth number, according to some sources, are lower than expected. For example, forecasters expected ~200,000 new jobs in March, not 162,000. And that’s in spite of the fact that BLS reported more census takers this year than usual. Not only does that potentially positively change the accuracy of the reporting of the numbers but it also increases the number of actual jobs created. And coincidentally, these happen to be six-month temporary jobs, not full-time permanent jobs. While adding temp jobs is a good way for businesses to pick up and a good way for folks to earn a bit of cash, it also may not be indicative of any real economic trend.

In a recent post, Former Secretary of Labor said something similar. Rob Reich said “These are six-month temp jobs, and they tell us nothing about underlying trends in the labor market. It’s hard to gauge precisely how many were hired — probably between 100,000 and 140,000, although some estimates put the hiring as low as 48,000. Almost a million census workers will need to be hired over the next few months. Subtract these, and today’s job numbers are good but nothing to write home about.”

Conventional wisdom pinpoints that demand for such temporary employees increases during recessions and during recoveries, so employers can get the help they need, while also shining a spotlight on their budgets and reigning in expenditures. This may mean that we’re still somewhere in the middle. Either way, there’s still a lot of uncertainty and unfortunately, nobody has the million dollar crystal ball to lead us into the future.

In light of that, I think I like some of the positive signs. After all, psychology plays a big part in market movements and perhaps a bigger one in its recoveries. There are a lot of different ideas and competing opinions out there, a few are from experts, a good number from those who have agendas, a lot with a different perspectives than you or I have, and most of them with different levels and sources of research.

And in the end, how you frame the issues will affect [and possibly even change] your viewpoint.

The New Labor Stats and Lessons for Leaders

Today’s slumping economy is haunting millions of Americans. Veterans of the workforce fear being let go and never finding a job again. Middle age employees worry about supporting their families and maintaining their careers. And students in both business and law schools are trying to understand what’s going on and adapt in order to find stable jobs upon graduation.

Today’s slumping economy is haunting millions of Americans. Veterans of the workforce fear being let go and never finding a job again. Middle age employees worry about supporting their families and maintaining their careers. And students in both business and law schools are trying to understand what’s going on and adapt in order to find stable jobs upon graduation.

With these thoughts at the front of everyone’s mind at the turn of the New Year, the Labor Department (DOL) just reported yesterday that 85,000 jobs were lost in December. This came as a pretty big surprise to economists who, after analyzing the net gain of 5,000 jobs in November, suspected that December would repeat the trend. And what’s worse is that reported numbers also show that more than 660,000 Americans dropped out of the labor force last month, meaning that the actual unemployment rate closer to ~10.5% instead of ~10.0%.

Although this change in calculation increases the unemployment rate to a near all-time high percentage, the bigger issue might be the fact that people are starting to drop out of the workforce, suggesting higher levels of pessimism than in 2009 and lower levels of hope than ever before. But if you think about it, this certainly makes a lot of sense. Many people have been closing in on a year out of work. And for the past twelve months, I’ve consistently heard so many people say that they have never seen things as bad as they are now.

Under this bright spotlight, America’s leaders now have to juggle crisis management, media and investor relations, new firm strategy, and most difficult of all, the daunting task of communicating the situation to its people. Inherent in this task is the fact that the people are vulnerable. Many people will become upset, others will react with anger, and most everyone will be uncertain. So while public leadership is something that has always hard, today it has become a near impossible challenge.

To be successful, the ability to communicate effectively will be critical. Modern leadership will less about the actual result than it is about gaining the trust of your workers and building a more unified organization. To do that, leaders will have to relate more closely to the issues of the people and also be able to deliver a compelling message. In times past, executives have overlooked this ability in favor of analyzing financial impact and making decisions more quickly. But that method of leadership will not work today. Instead leaders will have to be more connected with people and be more conscious of how people feel and how decisions will impact their economic situations. And so the best leaders will be those who not only analyze issues but those who also understand that what matters more is how you make others feel in the process.

To quickly clarify, actions always speak louder than words and leaders will also have to focus on results. After all, this is the only way any organization can survive. But in times of panic and adversity, focusing on your message and how you communicate it is often the best first step. So today, the leaders that emerge will be those who are good storytellers. They have a good understanding of the overall situation, and they will craft a compelling story, deliver that story effectively to the people, and then inspire them with hope for the future.

In the days to come President Obama (and CEOs of many companies) will embark on this ambiguous task. Though fiscal strategy and economic theory will be of critical importance in solving the issues, I hope that he reflects back to when he first became president and that he chooses talk more about his hope to rebuild the economy and create jobs than he does pure strategy.

And in the end, how he frames these issues will determine his success.

Reflecting On The Economic Challenges Of 2009

2009 was an interesting year. I left my consulting job in the spring after finally deciding to return to business school and law school. And what timing! The financial crisis had just struck and the fear of recession left all of the business world scrambling. At the same Barack Obama had just made political and legal history with his historic presidential election. I was pretty excited at the chance to study these economic and political events, especially since I’d be enrolling in a JD-MBA program. But it became hard to remain so excited as I watched layoffs, bankruptcies, and unemployment begin to take over.

2009 was an interesting year. I left my consulting job in the spring after finally deciding to return to business school and law school. And what timing! The financial crisis had just struck and the fear of recession left all of the business world scrambling. At the same Barack Obama had just made political and legal history with his historic presidential election. I was pretty excited at the chance to study these economic and political events, especially since I’d be enrolling in a JD-MBA program. But it became hard to remain so excited as I watched layoffs, bankruptcies, and unemployment begin to take over.

Ever since the past summer, I’ve tried to keep up with the news, chat with my classmates, and solicit perspectives from industry professionals trying figure out exactly what’s going on. To be honest, I’m still not 100% certain, maybe not even 50% certain of everything that’s happening, as I’m by no means an expert on economic or labor issues. But I suspect that one’s viewpoint is pretty correlated to their experiences in the labor market, and sometimes it can be hard to see outside of that perspective.

For example, I had a discussion with a classmate from the investment banking industry (economics defines this as skilled labor) during the first week of class. We were discussing how recruiting was supposed to be down 40% – 50% this year, and his perspective was that everyone should really embrace the situation. That hard times create new opportunities, give new learning experiences, and spawn new ideas and companies.

In a second conversation, I talked with a family member who works in a position that earns an hourly wage (economics defines this as unskilled labor) and his employer had cut back his hours. Because of his situation, he empathized a lot more with those who were unemployed, and he suspects that the recovery will be a longer and a more difficult process, and that speeding it up requires a more of a collaborative effort to help people to find jobs. I think both perspectives are pretty valid.

But whether or not you agree with either perspective, the common denominator is that we are in pretty tough times now and that recovery will depend both on a collaborative effort and a willingness to consider new opportunities to solve the problem. Until now, MBAs have been contributing to the recovery mostly by forecasting unemployment rates, analyzing spending patterns, and predicting the market turnaround. And JDs have been looking at similar issues, but focusing on finding ways to use their technical skills with the law and policy skills to create change.

My opinion–for what it’s worth–is that given certain structural problems in the modern economy, many of these financial and legal tactics, while useful, may ultimately prove to do nothing more than to cover the wound, rather than address the bigger cultural issues that in recent history have influenced our levels of consumption, debt, and greed.

If business and law schools want to continue to play a role in the recovery, they should reflect on how these issues fit into the country’s top priorities. Over the last few decades, MBAs have flocked to the finance industry and law school graduates to corporate law (a field that works directly with the finance industry) both lured by six-figure salaries that are 3x (and more) the average wage. In return, these smart graduates have worked in roles that emphasize getting things done over learning, charge excessive rates for services, and structure deals to maximize profit. And because there was so much profit, other industries looked up to the industry and soon followed suit.

This mentality eventually made its way into the mortgage industry, and needless to say, as soon as its companies began to offer credit, Americans began to borrow. A lot. They applied for new lines of credit, bought new homes and cars, and got big screen TVs and went on vacations. Unfortunately, this era of growth was in some respects artificial. In the end, people overextended themselves financially, and eventually found themselves in too deep once the economy slowed.

In November, the media and administration became optimistic again and claimed that we were rebounding from the crisis and that jobs would be back in no time. I’m not so sure I agree. From my perspective, it seems as though there are far too many people out of work now, and the average length of unemployment is closing in on a year in some locations, a number will stay on the rise given the decreasing number of jobs.

One thing I’ve learned in the past two years watching much of this unfold is that one of the most important resource a company has in the long-term is still its people. And that resource needs to be prioritized right alongside profitability. This is true especially in challenging times because even when profits and the stock market are down, the stock of a company’s employees can be up. People can collaborate to come up with new ideas, they help a company adjust, adapt and change with the markets, they learn and implement new technology and promote innovation, and they can work together to accomplish more than their individual capabilities.

Unfortunately, the majority of Americans aren’t afforded the training or education to fine tune their management or critical thinking skills, so they end up in lower paying jobs, can’t save their money, remain in deep debt, and can’t positively impact the economy, while only a minority of Americans at the top thrive. Not only is this socially troubling but many also argue that in the long run it may also economically less productive.

This is certainly the view of the Obama administration, which is why the president wants to focus more on education and training and make decisions based on longer-term public investment. In his view, the economy does best when all Americans have the chance to increase in skill and contribute to the market. Many people agree with him ideologically but many also object because of the costs and the up front time investment.

Obama is also working with companies to adjust compensation plans to make them more fair and to reduce layoffs in the workforce, both of which are controversial with economists. Maybe his strategy stems from the idealism or aversion to risk that comes along with being trained as a lawyer. Or perhaps it’s easier for him to think that broadly since he’s not feeling the pressure of a collapsing industry on his shoulders. Perhaps it’s also because his shareholders are comprised of the broader population, and not financial investors, so his policy incentives are different. Who knows? But the interesting part to me is that both the policy (JD) and economic (MBA) perspectives seem critical in analyzing economic recovery.

And so both MBAs and JDs can play a major role in helping save the economy. As MBAs continue to look for profitable deals, invest in companies, and architect executive pay plans, they are also called to leverage profits to create jobs, use investments to steer innovation, and think more broadly about human capital and not just executives. Similarly, lawyers also have dual obligations. And instead of simply relying on facts and mitigation of risk to make decisions, lawyers must think more critically about the issues. They need to weigh the economic issues with the resulting social issues, think about how those issues affect a broader range of people, anticipate a wider range of possible outcomes, and then balance risk with those outcomes to come up with new policy plans.

Easier said than done? Perhaps. Brokering a balance between profit and social value, when there are diverse points of view and competing agendas is rarely easy. To lead America down that path requires leaders who are not afraid of change and who deeply believe that social values are just as important as economic value. I suspect that given our economy, more people will be open to change and aware of social values than ever before.

Personally, the recession has certainly forced me to reflect on change. Having old colleagues, friends, and family members directly affected by the market has made me more empathetic to those still in the workforce, especially those who don’t have education as a buffer.

Society should also take time to do some reflecting. And perhaps in 2010, society will decide that instead of focusing so much on pricing strategies and stock market gains, it will also start to focus on creating opportunities for education, promoting generosity in the midst of competition, and maximizing human potential, and not just profits. And in the end, perhaps these will pave the way for recovery to a more stable economy.

Business schools and law schools should welcome the opportunity to be at the forefront of this change.

Labor Day And The Economy

Maybe it’s because I’ve been insulated from the outside world ever since I’ve started law school, but I’m quite surprised that I haven’t been hearing more about the labor and employment issues in the middles of the biggest economic recession in recent history. In light of the fact that it’s Labor Day tomorrow, I thought I’d share my thoughts on US labor and the economy.

Maybe it’s because I’ve been insulated from the outside world ever since I’ve started law school, but I’m quite surprised that I haven’t been hearing more about the labor and employment issues in the middles of the biggest economic recession in recent history. In light of the fact that it’s Labor Day tomorrow, I thought I’d share my thoughts on US labor and the economy.

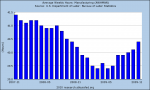

The latest employment figures came out September 4th, and the numbers are staggering. According to surveys, job losses continue to reach record levels — from 9.5% in July to ~9.7% now. Concurrently, merit increases have been frozen. In most industries, 4.0% pay increases have long been the standard … until now. Over the past year or so, wage growth has been closer to 0.5% and in some industries has flatlined at 0%. I saw these changes happening firsthand in my last consulting role, where more than half of my Fortune clients froze their merit increase pools, and nobody received salary bumps.

The unfortunate thing is that this number only represents those who still have jobs, and it doesn’t factor in that companies are decreasing worker’s hours, not paying bonuses, reducing 401ks, and demanding that employees go on furloughs (requiring workers to take unpaid vacations or to take one day off per week). I suspect about 20% of companies are employing these furloughs now, and at least to 50% of government companies. When I worked at the Attorney General’s Office this summer, the vast majority of people there were on the Friday Furlough plan. The US Post Office has requested that some employees take indefinite furloughs and they are offering incentive plans for people to retire as many as 10+ years early.

With all this in mind, I’m pretty surprised that I’m not hearing more about the economy or about the state of employment, especially this weekend. One explanation is the fact that “visible compensation†levels of the business class have not dramatically fallen. What I mean by “visible compensation†is the compensation numbers that make the Wall Street Journal or the news—CEO salaries, severance payments, number of stock options, and “expected†bonus levels.

But take caution in what you hear. From extensive experience studying the topic, I argue that these numbers are not representative of the American story. For the business class, what people don’t know is that cash compensation is usually a smaller fraction of a total pay package. Executives are usually highly reliant on “actual†bonuses and the appreciation value of stock options (not the delivery of options) as part of their paycheck. In fact, these often account for 50%-90% of their compensation packages. And despite Goldman’s recent record-breaking bonus payout this past summer, most firms are not handing out cash. Also, despite the thousands of stock options that executives are still receiving as part of their compensation arrangements, many of them are completely worthless. This is because option value for executives is based on the appreciation of the company, and in this economy companies are not appreciating. So despite popular perception and media frenzy about CEO pay, executives are also taking a huge cut in pay. That said, at least they can keep their heads above water with their 6-figure salaries even when everything else has gone awry.

For me, the real story is the middle class and the poor. The unemployment rate for these folks is a staggering 10%-16%, with African Americans and Hispanic Americans at the high end of the range. This is 2x to 3x higher than that of executives. The only outlier here is in the finance industry where everyone’s jobs and compensation are at risk.

Aside from job loss, the middle class’ portfolios are also declining. 401k plans have been dipping for the past year, health care plans are becoming more expensive, and the stock they do have is not performing well. But more important than that is the residential real estate bust, since homes are the primary assets of those in the middle class. Having spent a large amount of my life in two of the biggest real estate markets, California and Arizona, I’ve seen this first hand. In Arizona, the average decrease in home value is 35%-40%, the highest in the US. When I drive down the street of Arizona, I continuously notice homes for sale at 50% last year’s value and homes that have been foreclosed by the bank. On many streets, it’s half the homes. And California is no different. Home depreciation is hovering around the same range, even in nice neighborhoods like Berkeley, Santa Monica, and San Jose.

If so many Americans are losing their jobs, not getting increases in wages, loosing value in their homes, and subsequently in panic mode, what is going to incent people to spend money? I don’t know the answer, so I’ll leave that question to the economists working on it. What I do know is that that there needs to be a more focus on restoring the labor force in the middle class and because there hasn’t been most business are not safe. The one exception seems to be universities, especially top tier universities, where demand remains high, especially today as students hope to become more competitive for theses “odd†economic times. This is especially true for JD and MBA programs.

As I’ve mentioned in a couple of posts, I’m definitely fortunate to be headed back to school now. While here, I plan to take labor and employment classes at the law school as well as human capital and labor economics classes at the business school. I hope to be involved in these issues at the policy level one day down the line.

New Employment Stats and How Some MBAs, JDs, and Others Are Fairing

As everyone probably knows, the newest economic reports tell us that the official unemployment rate dropped from 9.5% to 9.4%. There seem to be two ways people are thinking about these numbers. Some people are happy to see the improvement and are growing optimistic about the future, especially those people with the MBA or JD qualifier. But there are an equal number of people who don’t feel that way and predict that things will continue to get worse. Which way of thinking is correct?

To be honest, I don’t know. I’m not an expert on labor issues, but I suspect that one’s perspective has a lot to do with what industry you work in, what school you went to, how long you’ve been at your current employer and your employment status. After chatting with lots of students, career centers, and professionals about career opportunities as a soon-to-be graduate student, my perspective is that the situation is still worse than it may seem.

First, the unemployment stats are not all inclusive. If you think about it for a minute, the unemployment stats don’t include those:

1) forced to work PT due to economic circumstances, but prefer FT work

2) with reduced FT hours. In some places FT is 32 hrs (20% reduction)

3) with expired unemployment benefits who are not current looking for work (i.e. maybe taking CFA exam, studying for Grad Tests, working in free internship, etc)

4) who’ve found new jobs that pay less or are not career jobs

5) headed back to school to avoid the economy (MBAs and JDs)

6) recently graduated in May 2008/9 that want to enter the workforce but haven’t found jobs yet (students, including MBAs & JDs)

If all these people are included, I suspect the “unemployment” numbers would raise dramatically, maybe to 2x what they are now.

Second, I’ve talked to a lot of MBAs since April, and there were a lot more than I would have expected that were still looking for jobs, even at the best ranked schools. I was completely shocked. The number of interns without jobs was as of this past spring was also staggering, because firms are taking full time hires before making intern offers. While the employment of interns may not seem as critical as graduates, not getting an internship will make one’s job search much harder the next year and for some may preclude certain job opportunities.

Third, in the legal field, a really large number of law firms have also curbed hiring. Many firms have decided to completely drop 1L summer hiring (1st year interns). I met an incredibly smart 1L from Stanford who I worked with at the Attorney General’s Office this summer, and she said that for the first time, many Stanford JDs didn’t get to summer at a corporate firm this year. She said it was the first time they struggled. I also lived with graduating JDs from Boston University this past year, and they have colleagues with really good grades still scrambling to finalize their plans. Many graduates were looking into non-paying internships in order to get work experience until they can find a paying job. What’s worse is that those jobs are not even guarantees, as the graduates now have to compete against 20 others for that non-paying job. As I said, the situation is a bit worse than it seems.

For me personally, I am not as worried about the economy just yet, because I’m headed to school for a few years. Hopefully I’ll be able to hide away from the worst of the recession. I also admit that I’m fortunate to be headed to a program with a track record of sending students to premier employers and a program where students take classes and can do research during the first summer, so there is less pressure to find a certain “type†of summer job.

But aside from my own situation, I have a lot of friends and family members who are affected, including JDs and MBAs. For that reason, I like to keep up with what’s happening and recently found a few stats that I found interesting:

1) More than 100k people have already used up their unemployment benefits (I have a former MBA co-worker and a JD friend that will have to worry about this soon)

2) These benefits range from 46 weeks in Utah to 79 weeks in Alabama, depending on the unemployment percentages in each state. This means that many residents have been unemployed and collecting benefits for well over a year now

3) By the end of Aug., an estimated 650k people will run out of unemployment benefits

4) By the end of 2009, the number is estimated to be 1.5 million. This number will include lots of MBAs from the financial services and other industries

Given those statistics, I’ve been doing a lot of reading and research about the economy. I recently found an article by late economist Arthur Okun (thanks to Robert Reich’s article for the reference), who once said that “a rule of thumb that every two percent drop in economic growth generates a one percent rise in unemployment.“ Robert said, that this is the first time that the rule no longer holds true. He said that it’s not even close this time.

Overall, I’m guessing that by the time I graduate in 2012, I will be living in a pretty different economy than I am today. I’m interested to see how that economy will look and thankful that I’ll have 3 years to observe, study, and prepare for what’s going to happen. What’s great about my JD-MBA program is that it will allow me to get a cross-functional, well-rounded perspective on everything that’s happening, as I’ll be able to interact with lawyers, politicians, judges, business people, recruiters, consultants, HR experts, academics, government officials, and students from a plethora of career backgrounds.

I’m definitely fortunate to be headed back to school during this defining period in our economy. Everyone who is applying this upcoming year should do the best they can to get in. Looking at the current economic environment and the unemployment trends, it’s probably going to be another tough year for applicants.

#EducationMatters

Please Vote

Recent Posts

Twitter Feed

Disclaimer

| S | M | T | W | T | F | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| « Jun | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |